Improving Performance with Server-Side Rendering: Concepts and Implementation

A deep dive into SSR architecture, performance metrics, and implementation strategies for building high-performance web applications.

We have all stared at it: the white screen of death, followed by a loading spinner that spins just long enough to be annoying, followed—finally—by the content we wanted. This is the hallmark of a heavy Client-Side Rendered (CSR) Single Page Application (SPA). For internal dashboards, this is acceptable. For public-facing products, SaaS landing pages, or content platforms, it is a bounce-rate generator.

As engineers building intelligent agents and micro-SaaS tools, we often focus heavily on backend logic and AI latency, ignoring the frontend delivery mechanism. But if your users close the tab before your agent loads, the backend performance is irrelevant.

In this article, we are going to dissect Server-Side Rendering (SSR). We will move past the high-level definitions and look at the request lifecycle, the impact on Core Web Vitals, and how to implement robust SSR using modern patterns like React Server Components (RSC).

The CSR Bottleneck

To understand why we need SSR, we must first look at the network waterfall of a typical CSR application (like a standard Create React App or Vue SPA).

- Browser requests document: The server returns an almost empty HTML shell.

- Browser downloads JS bundle: This is often huge (megabytes).

- Browser executes JS: The React/Vue instance boots up.

- Data Fetching: The client triggers API calls to fetch data.

- Rendering: Content finally appears.

The critical flaw here is the dependency chain. The user sees nothing meaningful until step 5. Search engines (crawlers) often stop at step 1 or 2, meaning your SEO is non-existent unless the crawler executes JavaScript (which Google does, but slowly and with limitations).

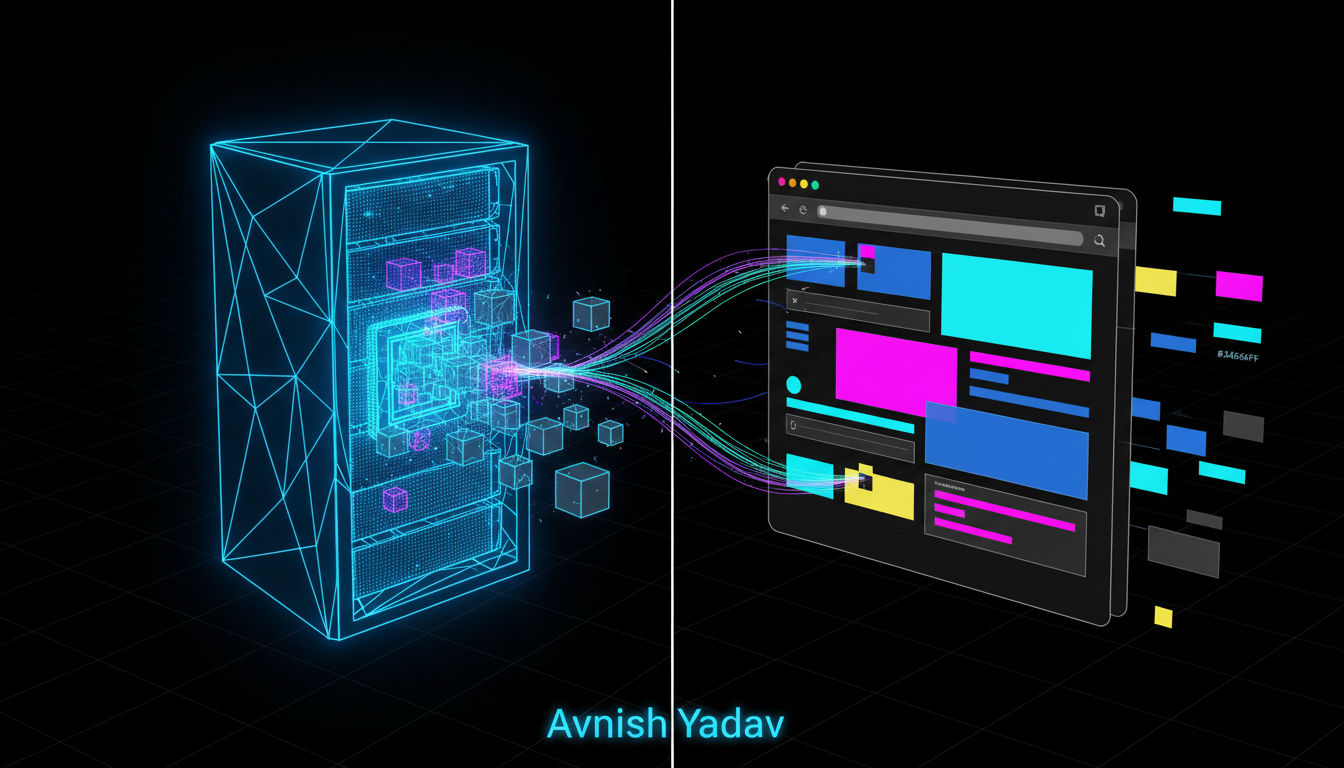

The SSR Architecture

Server-Side Rendering flips this model. Instead of sending an empty shell and a script tag, the server executes the component logic, fetches the necessary data, and generates the final HTML string before sending a response to the browser.

The Revised Lifecycle

- Browser requests document.

- Server processing: The server (Node.js/Edge Runtime) fetches data and renders React components to HTML.

- Response: The browser receives a fully formed HTML document. (User sees content here).

- Hydration: The browser downloads a smaller JS bundle to make the static HTML interactive (attach event listeners).

This shift dramatically improves First Contentful Paint (FCP) and Largest Contentful Paint (LCP)—two metrics vital for user retention and SEO ranking.

Implementation: Modern SSR with Next.js

While you can configure a custom Express server to render React strings, nobody builds that way in production anymore. It creates massive maintenance overhead. The industry standard for React-based SSR is Next.js, specifically utilizing the App Router and React Server Components (RSC).

Let's look at a practical implementation. In a traditional CSR approach, you would use useEffect to fetch data. In an SSR model, the component itself is asynchronous and runs on the server.

The Code Structure

Here is an example of a server component that fetches user data for a profile page. This code never runs in the browser.

// app/dashboard/profile/page.tsx

import { Suspense } from 'react';

import { getUserData, getRecentActivity } from '@/lib/db';

import ProfileSkeleton from '@/components/skeletons/ProfileSkeleton';

// This is a Server Component

export default async function ProfilePage() {

// This fetch happens on the server before the HTML is sent

const user = await getUserData();

return (

<main class="p-8">

<h1>Welcome back, {user.name}</h1>

<div class="grid grid-cols-2 gap-4">

<UserDetails user={user} />

{/* Streaming boundaries allow parts of the UI to load progressively */}

<Suspense fallback={<ProfileSkeleton />}>

<ActivityFeed userId={user.id} />

</Suspense>

</div>

</main>

);

}

// This component also runs on the server

async function ActivityFeed({ userId }: { userId: string }) {

// Introduce artificial delay to demonstrate streaming

const activities = await getRecentActivity(userId);

return (

<ul>

{activities.map((item) => (

<li key={item.id} class="border-b p-2">{item.action}</li>

))}

</ul>

);

}Analyzing the Performance Gains

In the code above, several optimizations occur automatically:

- Zero-Bundle-Size Data Fetching: The libraries used in

getUserData(like Prisma or a specialized SDK) are not included in the client-side JavaScript bundle. This keeps the site fast even on slow mobile networks. - Waterfalls on the Server: If we were fetching data on the client, we might have a waterfall (fetch user -> wait -> fetch activity). On the server, these fetches happen with low latency (usually within the same VPC), significantly reducing the total request time.

Advanced Concept: Streaming SSR

A common criticism of SSR is the "All-or-Nothing" problem. In traditional SSR, the server must finish fetching all data before it sends any HTML. If getRecentActivity takes 3 seconds, the user stares at a white screen for 3 seconds.

We solve this with Streaming (demonstrated by the <Suspense> boundary in the code above).

- The server immediately sends the HTML for the header and

UserDetails. - The browser renders this immediately.

- The server keeps the connection open. When

ActivityFeedfinishes fetching, the server streams that chunk of HTML to the browser, which pops it into the placeholder defined by theSuspensefallback.

This creates a perceived load time that is nearly instant, even if the underlying data is heavy.

SEO Implications

For the automated systems and micro-SaaS tools I build, organic traffic is the primary growth lever. SSR is non-negotiable here.

When a Googlebot crawler hits an SSR page:

- It receives the full title, meta descriptions, and semantic content in the initial response.

- It does not need to queue the page for JavaScript rendering (a secondary indexing process that can take days).

- Social media scrapers (Twitter cards, OpenGraph) work perfectly because the meta tags are populated server-side.

The Trade-offs: When NOT to use SSR

SSR is powerful, but it introduces complexity and cost.

- Server Costs: Unlike a static site hosted on a CDN (free/cheap), SSR requires a running compute process (Node.js container or Lambda function). For high-traffic sites, this scales costs linearly with users.

- Time to First Byte (TTFB): While FCP improves, TTFB can degrade if the server is slow to generate the page. Caching strategies (Redis or Vercel Data Cache) are essential to mitigate this.

- Hydration Mismatch: If your server renders one thing (e.g., a timestamp based on server time) and the client renders another (browser time), React will throw hydration errors, causing the app to flash or break.

Conclusion

Implementing Server-Side Rendering is a shift from "making it work" to "making it perform." By moving the heavy lifting to the server, we respect the user's device constraints and ensure our content is accessible to search engines.

For your next project, if you are building a dashboard behind a login, CSR is fine. But if you are shipping a tool that needs to be discovered and accessed quickly, adopt an SSR framework. The complexity of the setup pays dividends in user experience and SEO authority.

Comments

Loading comments...