Understanding the JavaScript Runtime: Event Loop, Call Stack, and Task Queue Explained

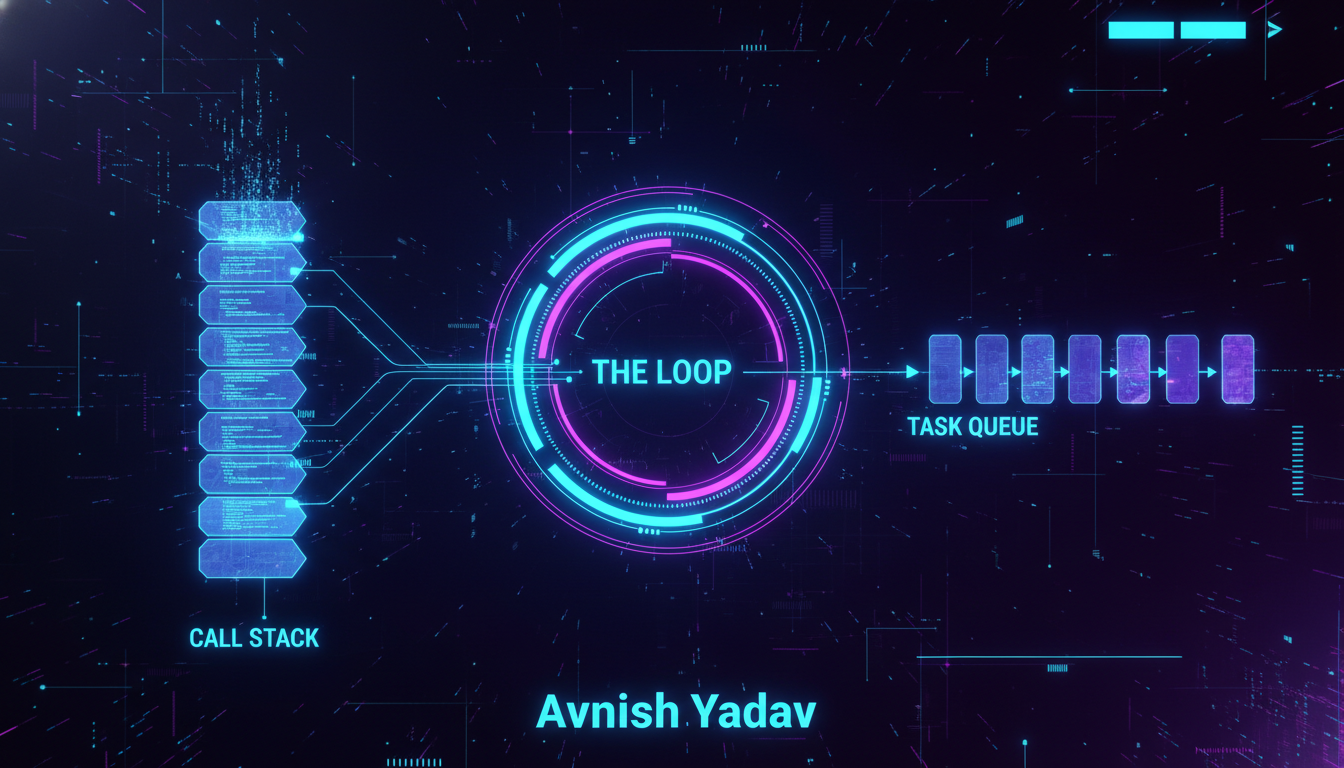

A comprehensive engineering guide to the JavaScript runtime environment. Learn how the Call Stack, Event Loop, and Task Queues interact to manage synchronous and asynchronous operations, and why Microtasks always win against Macrotasks.

If you have ever debugged a race condition in a Node.js scraper or wondered why a setTimeout of 0ms doesn’t execute immediately, you have collided with the reality of the JavaScript runtime. As developers, we write code that looks like it runs top-to-bottom, but the execution model is far more nuanced.

JavaScript is single-threaded. It has one call stack and one memory heap. In theory, if one function takes too long to run, the entire browser or server process should freeze. Yet, we build non-blocking, highly concurrent applications every day. How?

The answer lies outside the JavaScript engine itself—in the Runtime Environment. Whether you are in Chrome (V8) or Node.js (libuv), the mechanism that orchestrates chaos is the Event Loop. Let’s break down the architecture.

The Core Components

To visualize the runtime, we need to separate the engine (like V8) from the environment (the Browser or Node). The engine parses and executes code, but the environment provides the superpowers (APIs).

1. The Call Stack (The "Now")

The Call Stack is a data structure that records where in the program we are. If we step into a function, we push it onto the stack. If we return from a function, we pop it off.

function multiply(x, y) { return x * y;}function printSquare(x) { const s = multiply(x, x); console.log(s);}printSquare(5);The Execution Flow:

main()(global context) is pushed.printSquare(5)is pushed.multiply(5, 5)is pushed.multiplyreturns 25 and is popped.console.log(25)is pushed, runs, and is popped.printSquareis popped.

Since JS is single-threaded, if you put a heavy computation (like image processing or a massive while loop) onto the stack, the browser cannot render, listen to clicks, or make network requests. This is called blocking the stack.

2. Web APIs (The "Background")

So how do we handle network requests without blocking? We offload them. In the browser, the window object gives us access to Web APIs (DOM, AJAX, setTimeout). In Node, C++ APIs via libuv handle this.

When you call setTimeout, the JavaScript engine doesn't count the seconds. It hands that task off to the Web API and continues executing the next line of code immediately. This is why asynchronous code doesn't freeze your UI.

3. The Callback Queue (The "Waiting Room")

Once the Web API finishes its task (e.g., the timer expires or the HTTP request returns data), it doesn't shove the callback directly back into the execution flow. That would be chaotic. Instead, it pushes the callback into the Callback Queue (or Task Queue).

This queue follows a FIFO (First In, First Out) structure. The callbacks wait here, patiently.

The Event Loop: The Traffic Controller

This is the piece that ties everything together. The Event Loop has one simple job, which it repeats endlessly:

The Golden Rule: If the Call Stack is empty, take the first event from the Callback Queue and push it onto the Call Stack.

The Event Loop will never push a task from the queue to the stack if the stack is busy. This explains why a setTimeout(fn, 0) doesn't run immediately. It forces the function to wait until the current stack is clear.

Visualizing the Flow

Let's look at a classic interview question that trips up many mid-level developers.

console.log('Start');setTimeout(() => { console.log('Timeout');}, 0);console.log('End');What actually happens:

console.log('Start')pushes to Stack, executes, pops. Output: "Start".setTimeoutpushes to Stack. It registers a timer with the Web API and immediately pops.- The Web API sees the timer is 0ms, so it moves the callback (

() => console.log('Timeout')) to the Callback Queue. console.log('End')pushes to Stack, executes, pops. Output: "End".- The Stack is now empty. The Event Loop checks the Queue.

- The Loop moves the callback to the Stack.

console.log('Timeout')executes. Output: "Timeout".

Microtasks vs. Macrotasks: The Priority Lane

Here is where it gets interesting. Not all asynchronous tasks are created equal. ES6 introduced Promises, which use a different queue called the Microtask Queue (or Job Queue).

- Macrotasks:

setTimeout,setInterval,setImmediate, I/O. - Microtasks:

process.nextTick,Promise,queueMicrotask,MutationObserver.

The Revised Golden Rule: The Event Loop checks the Microtask Queue after every single operation and empties it completely before moving on to the Macrotask Queue.

Let’s verify this with code:

console.log('1: Script Start');setTimeout(() => { console.log('2: setTimeout');}, 0);Promise.resolve().then(() => { console.log('3: Promise 1');}).then(() => { console.log('4: Promise 2');});console.log('5: Script End');The Execution Order:

- 1: Script Start (Sync code)

- 5: Script End (Sync code)

- Stack is empty. Event Loop checks Microtasks.

- 3: Promise 1 (Microtask queue is higher priority)

- 4: Promise 2 (Chained promise is added to microtasks immediately)

- Microtask queue is empty. Event Loop checks Macrotasks.

- 2: setTimeout

If you create a recursive loop of Microtasks (e.g., a Promise that resolves another Promise infinitely), you will starve the Event Loop. The Macrotasks (like UI rendering or click events) will never get a chance to run, and the browser will freeze.

Implications for Automation Engineering

Understanding this architecture isn't just academic trivia; it impacts how we build systems.

1. Heavy Computation in Node.js

If you are building an automation agent in Node.js that processes large datasets or images, doing it on the main thread blocks the Event Loop. Incoming HTTP requests to your API will time out because the Loop is busy churning data on the Stack.

Solution: Use Worker Threads or offload heavy compute to a serverless function.

2. Rate Limiting and Queues

When orchestrating API calls, blindly using await in a forEach loop is inefficient (serial execution), while Promise.all can blow up the Call Stack or hit API rate limits instantly. Understanding the queue helps you implement batching or concurrency control (like p-limit) to manage the flow effectively.

Summary

JavaScript provides the illusion of concurrency through a clever system of queues and loops. The Engine does the work, the Web APIs handle the waiting, and the Event Loop coordinates the traffic.

- Call Stack: Executes the code. One thing at a time.

- Web APIs: Handle async operations outside the main thread.

- Task Queue: Holds callbacks from Web APIs (Macrotasks).

- Microtask Queue: Holds Promises. Has priority execution.

- Event Loop: If Stack is empty, run Microtasks, then run one Macrotask.

Next time you write an async function, visualize where it sits in the queue. It changes the way you debug.

Comments

Loading comments...