Architecting Scalable JavaScript: OOP Principles & Design Patterns

A deep dive into structuring JavaScript applications using OOP and industry-standard design patterns for better scalability and maintainability.

There is a distinct phase in every developer’s career when code stops being just a set of instructions and starts becoming a system. When you are writing a 50-line script to scrape a webpage, architecture doesn’t matter. But when you are building an AI automation agent that handles concurrent user requests, manages state, and interacts with multiple APIs, a functional spaghetti-code approach breaks down fast.

JavaScript is a multi-paradigm language. While Functional Programming (FP) has seen a massive surge in popularity (rightfully so for data transformation), Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) remains the backbone of architectural stability. It provides the vocabulary for state management, encapsulation, and abstraction.

In this post, I’m breaking down how I apply OOP principles and specific design patterns—Singleton, Observer, and Module—to build scalable automation tools and micro-SaaS applications.

The Shift: From Scripts to Architecture

The biggest misconception in modern JavaScript is that classes are just "syntactical sugar" over prototypes and should be avoided in favor of pure functions. While technically true regarding prototypes, classes offer a mental model that maps incredibly well to real-world entities.

When building an automation system, I don't think in functions; I think in Agents, Managers, and Connectors. OOP allows us to model these entities directly.

Core OOP Principles in Modern JS

Before diving into patterns, we need to utilize modern JavaScript features to enforce OOP principles, specifically Encapsulation.

In the past, we relied on underscores (_privateVar) to signal privacy. Today, we use native private class fields (#).

class AgentConfig {

#apiKey;

constructor(key) {

this.#apiKey = key;

}

getSafeConfig() {

return {

status: 'active',

// API key remains hidden from the outside scope

hasKey: !!this.#apiKey

};

}

}

This isn't just syntax; it's a structural guarantee that sensitive state cannot be mutated unpredictably. This is the foundation upon which we layer our design patterns.

1. The Module Pattern: The Foundation of Structure

The Module Pattern is arguably the most important pattern in JavaScript history. It allows us to split code into smaller, reusable pieces while keeping variables private and explicitly exposing a public API.

Evolution: From IIFE to ES Modules

Historically, we used Immediately Invoked Function Expressions (IIFEs) to create closures. Today, ES6 Modules are the standard, but the concept of the pattern remains vital for internal architecture.

When I build a micro-service, I treat every feature as a module that exposes only what is necessary.

// database-connector.js (The Module)

const dbConfig = {

host: 'localhost',

retries: 3

};

// Private implementation detail

function connect() {

console.log(`Connecting to ${dbConfig.host}...`);

}

// Public API

export class DatabaseService {

constructor() {

// We invoke private logic here

connect();

}

query(sql) {

console.log(`Executing: ${sql}`);

return [];

}

}

Why it matters for Automation

In automation, you often have distinct domains: Content Generation, Social Posting, and Analytics. By strictly adhering to the Module pattern, you prevent the "Content" logic from accidentally modifying the "Social Posting" configuration. It creates boundaries.

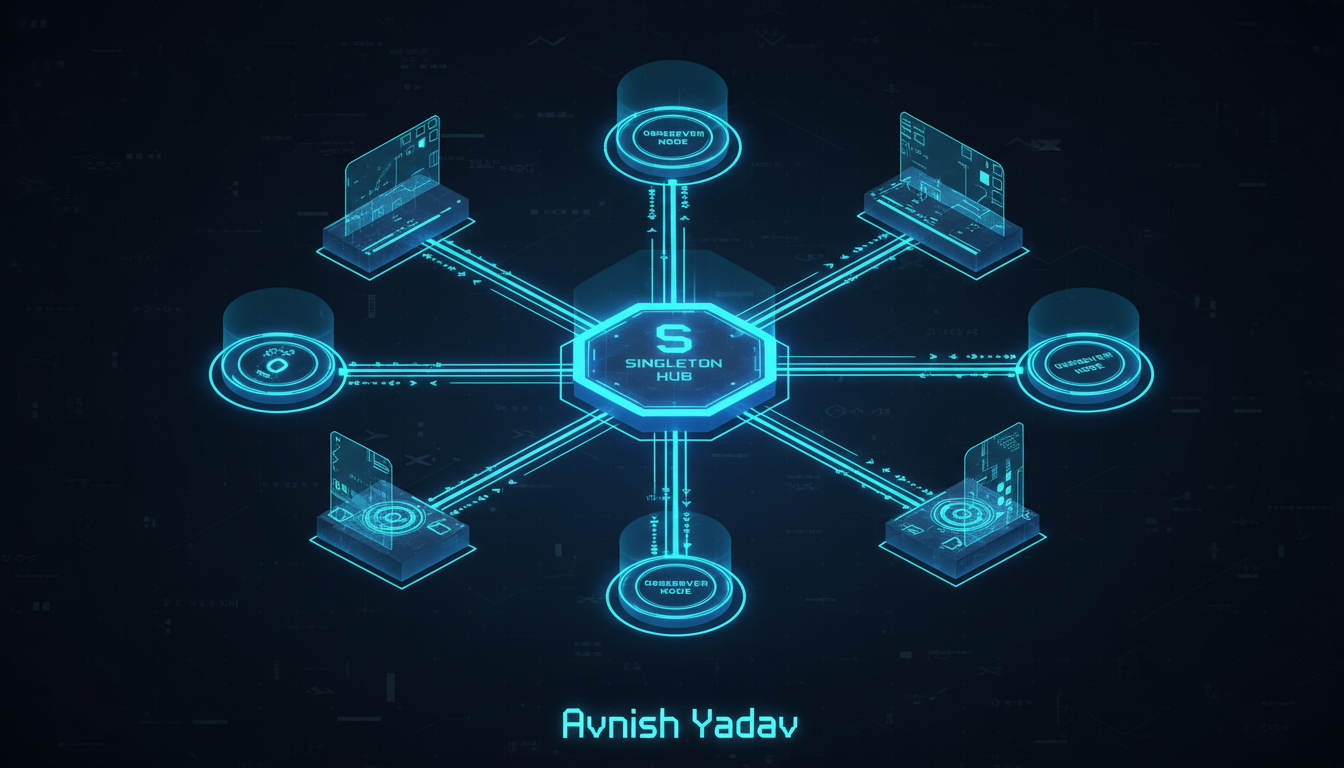

2. The Singleton Pattern: Managing Shared State

The Singleton pattern ensures that a class has only one instance and provides a global point of access to it. In the context of building agents or backend services, this is non-negotiable for things like Database Connections, Loggers, or Configuration Managers.

You do not want to instantiate a new connection pool every time a user makes a request.

Implementation in JavaScript

JavaScript makes Singletons incredibly easy because modules are cached by the runtime. However, to be explicit within a class structure, we can enforce it logically.

class Logger {

constructor() {

if (Logger.instance) {

return Logger.instance;

}

this.logs = [];

Logger.instance = this;

// Prevent modification of the singleton instance

Object.freeze(this);

}

log(message) {

const timestamp = new Date().toISOString();

this.logs.push({ timestamp, message });

console.log(`[${timestamp}] ${message}`);

}

getHistory() {

return this.logs;

}

}

// Usage

const loggerA = new Logger();

const loggerB = new Logger();

loggerA.log("System init");

console.log(loggerA === loggerB); // true

console.log(loggerB.getHistory().length); // 1

The Builder's Perspective

Use Singletons sparingly. They are essentially global state, which makes testing difficult. I use them strictly for infrastructure (Logging, DB, Config) and never for business logic (like a specific User session).

3. The Observer Pattern: Decoupled Event Architecture

If you are building an automation agent, you are essentially building an event-driven system. "When a new lead arrives -> Notify Slack -> Add to CRM -> Send Email."

Hardcoding these relationships creates rigid, brittle code. The Observer Pattern (often implemented via Pub/Sub) allows a subject to notify a list of observers when its state changes, without knowing who those observers are.

Building a Custom Event System

While Node.js has an EventEmitter, understanding how to build this pattern helps you structure complex front-end or logic layers.

class EventManager {

constructor() {

this.listeners = {};

}

subscribe(eventType, callback) {

if (!this.listeners[eventType]) {

this.listeners[eventType] = [];

}

this.listeners[eventType].push(callback);

}

notify(eventType, data) {

if (!this.listeners[eventType]) return;

this.listeners[eventType].forEach(callback => {

callback(data);

});

}

}

// The Subject (e.g., A Lead Capture Form)

class LeadSystem {

constructor(eventManager) {

this.events = eventManager;

}

newLead(leadData) {

console.log("New lead received.");

// The system doesn't know what happens next, it just notifies.

this.events.notify('lead:created', leadData);

}

}

// Usage

const events = new EventManager();

const crm = new LeadSystem(events);

// Observer 1: Slack Notifier

events.subscribe('lead:created', (data) => {

console.log(`[Slack Bot]: Sending alert for ${data.name}`);

});

// Observer 2: Email Sequence

events.subscribe('lead:created', (data) => {

console.log(`[Email Bot]: Queuing welcome email to ${data.email}`);

});

crm.newLead({ name: "Avnish", email: "avnish@example.com" });

Why this scales

Six months from now, when you need to add a feature to "Add Lead to Google Sheets," you don't touch the LeadSystem code. You simply subscribe a new observer to the lead:created event. This adheres to the Open/Closed Principle: open for extension, closed for modification.

Practical Application: The "Bot Controller"

Let’s put it all together. How do these look in a real production file for a bot I might write?

I would use a Singleton to manage the configuration (API keys). I would use the Module pattern (classes) to define the individual agents (Scraper, Writer). And I would use the Observer pattern to let the Scraper tell the Writer when data is ready.

// State Management (Singleton)

import Config from './Config';

// Logic Units (Modules/Classes)

import ScraperAgent from './ScraperAgent';

import WriterAgent from './WriterAgent';

// Orchestration

class BotController {

constructor() {

this.config = new Config();

this.scraper = new ScraperAgent();

this.writer = new WriterAgent();

}

init() {

// Using Observer logic (simplified)

this.scraper.on('data_scraped', (content) => {

this.writer.draftPost(content);

});

this.scraper.start(this.config.targetUrl);

}

}

Conclusion

Design patterns aren't academic theory; they are tools for managing complexity. As you move from writing scripts to building systems and products, your ability to organize code determines the lifespan of your project.

Start small. Next time you need a global configuration, try a Singleton. Next time you have tight coupling between two functions, try the Observer pattern. Build systems that are easy to reason about, and the automation will follow.

Comments

Loading comments...